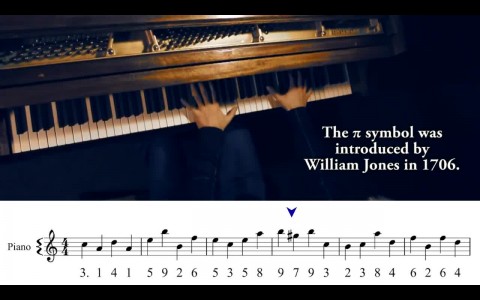

In what could possibly be the first case of its kind, a young girl has been filmed playing the piano while being fast asleep. This amazing feat took place in Napier in New Zealand’s North Island in July 2015. The protagonist, a 13-year-old girl by the name of Isabelle, had gotten up from bed, sleep walked to her living room, and played a tune on her upright piano. While she was clearly in slumber, as could be witnessed from the occasional snores that punctuated the tune, Isabelle had her fingers firmly on the keys. The young pianist eventually played a tune that she did not recognise and later attributed to a mix of something she already knew and something she had created herself. The video, which was posted by her uncle, became an instant hit, garnering 24,000 views in 24 hours. It received prominent feature in The New Zealand Herald and was also picked up by news websites in Australia around the world.

Sleepwalking is a common occurance in children. It affects both boys and girls and they typically outgrow it in their teenage years. It can be caused by a number of reasons, including fatigue, illness and stress and normally happens in Stages 3 and 4 of the sleep cycle. These are the phases of deep sleep, just before the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) stage starts. A child who experiences sleepwalking normally wakes up within an hour or two of falling asleep and is up and about for a maximum of 30 minutes. During this period, he or she may wonder about and generally do things that one would normally do at that hour. Stories of children talking and singing in their sleep have been well-documented, but none of anyone playing the piano while sleepwalking had previously been known till Isabelle’s case surfaced on the Internet.

While the aspiring pianist’s encounter makes for interesting trivia for both pianists and non-pianists alike, this case highlights one important aspect of piano-learning. For decades, pianists have used the term muscle memory to describe how veteran pianists are able to play almost effortlessly. Contrary to the meaning it implies, muscle memory has nothing with do with body muscles. This misnomer refers to the ability of the body to remember specific steps that it needs to take in order to complete a task. Students of personal development training learn that humans have a conscious mind and a subconscious mind. While the mind is conscious of actions that the body takes when learning a new skill, these actions become second-nature once they have been performed frequently enough. This is because these actions have been transferred from the conscious mind to the subconscious mind and the body takes little effort when executing actions stored in the subconscious mind. To illustrate this concept in layman terms, imagine a child who is learning to cycle. Cycling as a skill is new to her and she struggles for the first few tries. Eventually, she succeeds and can cycle with less difficulty. As she grows older, her body allows her to cycle effortlessly once she gets onto the bicycle, leaving her to focus on other things like road safety and watching out for pedestrians. This happens because the actions needed to push the bicycle forward have been imprinted in her subconscious mind. The skill has been mastered and cycling has now become second-nature to the girl. She has developed what is known as muscle memory.

In Isabelle’s case, she has clearly developed muscle memory. It allowed her to play the piano without noticeable difficulty even though she was fast asleep. She is yet another testimony of the opinion that pianists – and musicians in general – develop muscle memory with consistent practice. Established pianists are able to harness muscle memory to their advantage as the tunes manifest themselves easily, sometimes even without the need for the pianists to refer to sheet music, leaving them to focus on other aspects of piano-playing.