“Originally we had in mind what you might call an imaginary beauty, a process of basic emptiness with just a few things arising in it... And then when we actually set to work, a kind of avalanche came about which corresponded not at all with that beauty which had seemed to appear to us as an objective.”

The above is an extract from Silence: Lectures and Writings by John Cage, an American composer who lived in the 20th century. Based in New York City, John Cage was an experimental music theorist who deviated from mainstream music and sought to redefine music as we know it.

He dwelled on the abstract and explored the relationship between music and silence, even going as far as to question established musical preconceptions. Cage was perhaps best known for his 1952 “silent” piece, 4’33”.

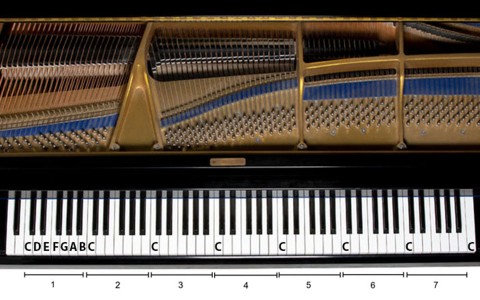

4’33” is read “four minutes and thirty three seconds” and is sometimes known simply as 433. It is a piece that defies the conventions of classical music. When performed by a soloist, this composition sees the performer take the seat at the piano but doing absolutely nothing with it.

During the three movements, the keys are left untouched and the score precisely reflects this anomaly by featuring perpetual rests. In a performance by William Marx, he starts a timer at the beginning of each movement, only to let the time lapse without playing a single note, before closing the keyboard lid, reopening it and starting the next movement.

Even though 4’33” as a composition does not produce tangible music as a direct result of keyboard action, it is far from being a silent piece.

During the almost five-minute-long performance, ambient noise from around the piano can be heard. This might be the whirl of the airconditioner, the coughs of members in the audience, whispers between bewildered people or even traffic from outside the performance hall.

Being a piece that is totally void of any keyboard-produced music, 4’33” switches the attention from the performer to the audience. Because of this inherent characteristic, which sees the performance picking up subtle, otherwise-overlooked background noise present in different locations with different people in attendance, no two pieces are exactly the same.

This challenges the very premise of a music performance, which by convention dictates that the performer, with all his associated merits and flaws, as well as the very musical piece which is played, are the foci of delightful enjoyment as well as intense scruntity.

Cage’s piece pushes the boundaries of the human understanding of music and by extension, the meaning of music as a performance art. This is analogous to the meaning of the term “the deafening silence”, which though abstract, is not totally void of logic.

By shifting the focus of the conscious mind away from external noise, one is forced to listen to noise coming from within oneself. Doing so breaks the traditional concept of listening, effectively allowing the apparently simple art of listening to transcend the boundaries between the physical and inner worlds.

Cage’s unusual interpretation of music can be attributed to the influence that came from an Indian music teacher, Gita Sarabhai. Sarabhai is known for her famous line, “The purpose of music is to quiet and sober the mind, making it susceptible to divine influences.”.

Evidently, this profound statement had a defining role in Cage’s future works. He went on to create the piece Silent Prayer, which he saw as his way of cutting though the noise of daily commercial activities that were representative of materialistic America. The result was the unearthing of the sacred silence hidden in the stillness which prevailed under the many layers of unwelcome noise.

Cage’s attempt at redefining music is not without its controversy. Many have questioned the wisdom of Cage’s approach and some have gone as far as calling 4’33” a “gimmick”.

Indeed, a concert-goer expecting an exciting performance in exchange for premium paid for a ticket may find himself shortchanged as soon as he settles in his seat. Still, many have extolled the virtues of Cage’s creations and the newly-discovered dimensons associated with the appreciation of the performing arts.

If anything, they have evoked intellectual debates that question the very domains that govern the meaning of music and argue that time, manifested in its full glory when listening to an apparently silent piece like 4’33”, should be viewed as a valid dimension of music and given as much importance as the audible notes that one hears. This view then brings about the question of whether silence should even be considered a form of music. Clearly, there is no answer to this profound question.

Cage’s 4’33” is hardly the last composition that pushed the boundaries of the understanding of music. In 1969, Alvin Lucier created a tape recording known as I Am Sitting in A Room, which was essentially a series of recordings of preceding recordings.

Lucier read a script into a tape recorder, then played the recording on a different machine and had the playback recorded. He repeated this process 50 times. The result was a narrative that slowly faded into obscurity with each passing piece as it got swallowed by the acoustic cackles and other audible distractions that were introduced as a result of the use of the recording device. Following in his footsteps, Lucier’s wife performed a visual representation of the process when she made copies of preceding copies of a document using an early version of the Xerox copier.

Like Cage’s 4’33”, Lucier’s attempt at redefining sounds through his tape recorder challenged man’s traditional notions about sounds as we know them. It brought scruntiny into the ways humans defined sounds and music and gave prominence to the concepts of producing simple things in non-conforming ways and leaving things to chance. Like Cage’s 4’33”, it also inevitably gave rise to the question of whether non-salient sounds like silence and interference should be considered music at all. There is no simple answer to this question.

In an apparent show of the widespread appeal of 4’33”, this infamous piece has given rise to an interesting global movement. This exercise involves having people from around the world contribute their own 4’33” recordings. The results have been as varied and colourful as highway noise and the chime of bells in a subway carriage. True to the essence of leaving things to chance, no two contributions are ever the same.

John Cage’s controversial pieces have evoked great human imagination and sparked debates on the most abstract of matters. Cage would be comforted to know that 64 years after it was composed, his unique composition continues to intrique human minds.